Drilling and stray natural gas migration

From Wikimarcellus

| Revision as of 23:15, 10 November 2012 Tcopley (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 23:18, 10 November 2012 Tcopley (Talk | contribs) (→Marcellus Shale Coalition Recommended Practices on shale gas) Next diff → |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| Under this Act, whenever there is any contamination of drinking water, the well operator is held liable for replacing the damaged water supply. Operators are also required to notify PDEP promptly in the event of any complaints regarding natural gas migration. Emergency responders are to be summonsed when high concentrations of gas are noticed. | Under this Act, whenever there is any contamination of drinking water, the well operator is held liable for replacing the damaged water supply. Operators are also required to notify PDEP promptly in the event of any complaints regarding natural gas migration. Emergency responders are to be summonsed when high concentrations of gas are noticed. | ||

| - | ===Marcellus Shale Coalition Recommended Practices on shale gas=== | + | ===Marcellus Shale Coalition Recommended Practices on stray gas incidents=== |

| The Marcellus Shale Coalition is a membership organization made up of natural gas exploration and production companies as well as suppliers to that industry. In October, 2012 the Coalition issued a guidance document on how operators should handle stray gas incidents. Operators are advised to act very proactively in event of any report of gas migration. | The Marcellus Shale Coalition is a membership organization made up of natural gas exploration and production companies as well as suppliers to that industry. In October, 2012 the Coalition issued a guidance document on how operators should handle stray gas incidents. Operators are advised to act very proactively in event of any report of gas migration. | ||

Revision as of 23:18, 10 November 2012

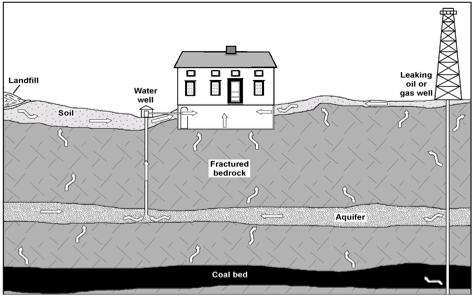

Stray natural gas migration refers to the movement of natural gas (mostly methane) through bedrock and soil. It can leak from a variety of sources, including reservoir rock, coal seams, landfill, or pipelines. It can also occur from drilling any well--gas, oil or water--as well as from abandoned wells. Whenever the water table is penetrated by drilling a well, methane gas may be given an escape route. It tends to move from areas of high pressure to low.

Contents |

Identifying Stray Gas

Stray gas is quite common in regions of North America that are undergirded by hydrocarbon deposits, such as in southwestern and northeastern Pennsylvania. It can be found throughout the central and northern Appalachian Basin. When it occurs, it can be broken down into three main categories:

- Sub-surface microbial gas. These originate in deep sea sediments and may be identified as drift gas.

- Near-surface microbial gas often from landfills or naturally occurring marsh gas.

- Thermogenic gas consisting of natural gas or coal-bed gas.

These gasses can blend together into a mixture. The origin of stray natural gas may only reliably be determined by its chemical signature.

Factors Affecting Gas Migration

The general rule is that stray natural gas moves from areas of high pressure to ones of lower pressure. However several factors can, come into play that influence migration. These include changes in barometric pressure, porosity and permeability of soil and bedrock, temperature differentials, rain or snow.

Stray Gas Regulatory Environment

Pennsylvania has taken an aggressive stance towards regulating stray gas originating from drilling operations. Obviously, there is little that can be done to regulate naturally-occurring gas migration. The state issued new drilling regulations in 2011 to help combat gas leaks from drilling operations.

The Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Act

The Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Act of 2011 automatically assumes whenever a new well is drilled within 1,000 feet of a drinking water supply, and contamination such as stray gas or chemical occurs within six months of drilling, that the operator is at fault. Thus, in order to either establish or else avoid blame, it is important for both the water supply owner/homeowner in addition to the well operator to obtain test samples of the drinking water before drilling begins. Well operators must report any incidents of contamination to PDEP within 24 hours once it is in fact discovered.

Regulation of Well Casings

The Act focuses regulating well casings and cementing as one possible source of stray gas, and specifies construction standards and requirements that bring Pennsylvania' drilling regulations up to the same standard as several other states. The purpose is to provide greater protection for home and property owners from contaminated drinking water. Also blow-out preventers--essentially large valve or a series of valves that can be triggered remotely to close-off a well bore--are required on all natural gas wells.

Operator Held Liable

Under this Act, whenever there is any contamination of drinking water, the well operator is held liable for replacing the damaged water supply. Operators are also required to notify PDEP promptly in the event of any complaints regarding natural gas migration. Emergency responders are to be summonsed when high concentrations of gas are noticed.

Marcellus Shale Coalition Recommended Practices on stray gas incidents

The Marcellus Shale Coalition is a membership organization made up of natural gas exploration and production companies as well as suppliers to that industry. In October, 2012 the Coalition issued a guidance document on how operators should handle stray gas incidents. Operators are advised to act very proactively in event of any report of gas migration.

The group advises its members to make a site survey as soon as possible after being notified of a stray gas incident. It should interview workers on the scene and make a reconnaissance survey. Operators are expected to be good communicators with owners, emergency responders (if required) and state regulatory agencies. In the event of a critical incident, emergency response organizations will need to be made fully aware so that evacuation and/or ventilation can take place.

The initial reconnaissance survey should include monitoring all buildings, out buildings and water wells to detect possible migration paths for the gas

If necessary, the operator should take immediate action to vent any water wells with high concentrations of dissolved methane, install monitors and alarms when needed, and/or provide an alternative drinking water source for the home owner/landowner.

The operator should essentially document everything about the incident, and in fact it may be a state requirement to do so. The end objective is to obtain permission from the state regulatory agency to close its file on the incident. An operator can document either that the migrating gas was already there, or else if it does have some responsibility, then to provide a remedy for the migration.

Naturally Occurring Stray Gas Migration

Not all cases of natural gas migration are caused by drilling activity. Gas bubbles percolating in water wells and gas seeps have been endemic in certain areas such as northeast and southwest Pennsylvania since time immemorial. Their causes are diverse, but none are related to present day natural gas development going on in the area. Homeowners who live in areas where gas migration is an issue generally realize that they need to avoid dangerous build-ups of methane gas. The two most common methods of getting rid of it are through venting and aeration.

Venting

Venting can be aided by use of a fan to pump the methane outside or via an airstream to dilute the methane at the point of entry into a confined space. A water well's casing and cap may be vented to avoid accumulation in distribution lines, pressure tanks, water treatment equipment, water heaters, or in a well house.

Aeration

Aeration is generally more effective than venting in dealing with dissolved methane in groundwater. The basic idea of aeration is when air gets pumped into the water, methane gas is forced out, and it generally is the only way to reduce methane concentrations to lower than 3 to 5 ppm (parts per million). These may consist of spray aerators that mist the well water into an enclosed tank, but may range at the high end to tower units that collect and disburse the accumulated gas.

Chlorinationn required

Anytime you open a sealed water system as with venting or aeration, you introduce the possibility of bacterial contamination. Water is generally then sanitized in a tank through chlorination.